Summary

Summary

The Netherlands continues to be a significant transit point for drugs entering Europe (especially cocaine), an important producer and exporter of synthetic drugs (particularly Ecstasy and amphetamines), and an important consumer of most illicit drugs. U.S. law enforcement information indicates that the Netherlands still is by far the most significant source country for Ecstasy in the U.S. The current Dutch center-right coalition has made measurable progress in implementing the five-year strategy (2002-2006) against production, trade and consumption of synthetic drugs announced in May 2001. For example, there has been a significant increase in Dutch seizures of Ecstasy pills from 3.6 million in 2001 to six million in 2002 (last year for statistics). In July 2003, the National Criminal Investigation Department (Nationale Recherche) was set up with the key objective of enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of criminal investigations and international joint efforts against narcotics trafficking. Operational cooperation between U.S. and Dutch law enforcement agencies is excellent, despite some differences in approach and tactics. Dutch popular attitudes toward soft drugs remain tolerant to the point of indifference. The Dutch government and public view domestic drug use as a public health issue first and a law enforcement issue second.

Cocaine Couriers

Cocaine Couriers

Despite fierce political opposition, the Dutch Parliament approved Justice Minister Donner’s plan to close down Schiphol airport to cocaine smuggling from the Caribbean on December 10, 2003. An estimated 20,000-40,000 kilos of cocaine, destined primarily for the European market, are smuggled annually through Schiphol (Dutch cocaine use is estimated at 4,000-8,000 kilos annually - in 2001 and 2002, more than 3,500 drug couriers were arrested and some 10,000 kilos of cocaine seized at the airport). Donner hopes to achieve 100% interdiction of the drugs coming into Schiphol on targeted high-risk flights from the Netherlands Antilles, Aruba and Suriname. He told the Second Chamber of Parliament on December 3, 2003, that, as a result of the 100% controls of passengers, luggage, freight and aircraft, the number of drug couriers is expected to rise significantly, fearing inadequate law enforcement capacity to handle the number of arrests. According to Donner, this justifies a temporary adjustment in prosecution policy - a certain category of drug couriers will not be prosecuted. He explained that criteria would be drawn up, which will not be made public in the interest of criminal procedures. However, couriers failing to meet these criteria will be prosecuted. (Unconfirmed reports suggested that only smugglers caught with 3 kilos or more are prosecuted.) Donner stated that summoning drug couriers in court at a later date would not be a solution, because this would also put a heavy burden on the Dutch judiciary. He did pledge the Chamber an early assessment of his proposals. Relevant data of drug couriers will be made available to airlines, which will be responsible for taking special measures against these persons, including an indefinite flight ban. Despite opposition within Donner’s own Christian-Democratic Party (CDA), the Second Chamber adopted his proposals on December 10, 2003.

The plan went into effect on December 11, and, during the first five days, 120 couriers were arrested on flights from the Netherlands Antilles, of whom 31 were released without a summons after drugs were recovered. The remaining 89 cases are being investigated or prosecuted. In addition, 104 potential passengers were turned away by the airlines and 375 passengers did not turn up. About 120 kilos of drugs were seized. During routine checks on flights from Suriname, 22 couriers were arrested, one of whom carried 14.5 kilos of cocaine.

Ecstasy Offensive

Ecstasy Offensive

In July 2003, Justice Minister Donner published a progress report on the implementation of the five-year (2002- 2006) action plan against production, trade, and consumption of synthetic drugs. According to the report, six million Ecstasy pills were seized in 2002 compared to 3.6 million in 2001, and the number of dismantled Ecstasy laboratories rose to 43 in 2002 from 35 in 2001. The increase in Ecstasy seizures was attributed to intensified controls at Schiphol airport by the special team of Dutch customs and the military police (more than one million pills seized there in 2002), the introduction of five special police Ecstasy teams (total manpower: 90), and increased staffing at the Fiscal Intelligence and Investigation Service-Economic Control Service (FIOD-ECD). The progress report shows that the measures announced in the action plan are well underway. According to the 2002 annual report of the Unit Synthetic Drugs (USD), the five XTC teams conducted 36 investigations in 2002 and arrested some 76 suspects.

The chemical precursor PPK is the principal precursor used by Dutch Ecstasy laboratories. It comes mainly by sea from China through Rotterdam port. Due to human rights concerns, the Dutch government shares only limited information of an administrative nature with China. A Memorandum of Understanding formalizing this information- sharing arrangement was submitted to the Chinese in October 2003. No response has yet been received. The MOU states that China will keep the Netherlands informed regarding the progress and results of investigations that have been instigated on the basis of this administrative information. In addition to working directly with the Chinese, the Netherlands is an active participant in the INCB/PRISM project’s taskforce.

Cannabis

Cannabis

According to the fourth survey on coffeeshops in the Netherlands, published in October 2003, there were 782 officially tolerated coffeeshops at the end of 2002, which is a 3 percent drop over 2001, principally in the four major cities. About 73 percent of Dutch municipalities do not tolerate any shops at all, according to the study. In early 2004, Justice Minister Donner, whose CDA party has advocated closing of coffeeshops, is expected to publish a Cannabis Policy Paper, which should discourage cannabis use.

The 2002 National Drug Monitor shows that the number of recent (last-month) cannabis users in the Dutch population over the period 1997-2001 rose from some 326,000 to 408,000, or 3 percent of the Dutch population of 12 years and older (of a total population of 16 million). The largest increase is reported among young people aged 20-24, while use among the 12-15 year-old age group remained limited and hardly changed from 1997. Life-time prevalence (ever-use) of cannabis among the population of 12 years and older rose from 15.6 percent in 1997 to 17 percent in 2001. The average age of recent cannabis users is 28 years.

On November 27, 2003, the Netherlands agreed on an EU framework decision on harmonized sentencing of drug traffickers. Under the agreement, the maximum penalty for possessing a small quantity of cannabis will be raised from one month to one year imprisonment. The agreement, if ratified by Dutch parliament, would allow the Netherlands to maintain its coffeeshops.

Medicinal Cannabis

Since March 17, 2003, doctors are allowed to prescribe their patients medicinal cannabis. Two suitable government-controlled cannabis growers have been contracted, and, as of September 2003, the drug can be bought from pharmacies. The Health Ministry’s Bureau for Medicinal Cannabis controls quality and organizes the distribution. According to the Health Ministry, cannabis may have a favorable effect on seriously ill patients but the government recognizes the therapeutic effects of medicinal cannabis have not been proved and research continues.

Cultivation and Production

Cultivation and Production

About 75 percent of the Dutch cannabis market is Dutch-grown marijuana (Nederwiet), although indoor cultivation of hemp is banned, even for agricultural purposes. Amsterdam University researchers estimate that the Netherlands has at least 100,000 illegal home growers of hashish and marijuana, with the number increasing. Together they produce more than 100,000 kilos of soft drugs and are the largest suppliers of coffeeshops, according to the study. The estimates are based on a significant rise in the number of lawsuits and police raids. Although the Dutch government has given top priority to the investigation and prosecution of large-scale commercial cultivation of Nederwiet, tolerated coffeeshops appear to create the demand for large-scale commercial cultivation.

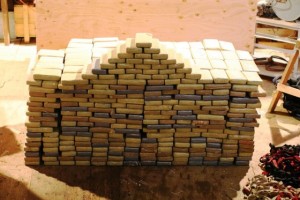

The Netherlands remains one of the world’s largest producers of synthetic drugs. In 2002, the USD registered a total of 740 seizures of synthetic drugs around the world, of which 205 (some 30 percent) took place in the Netherlands. Of the remaining seizures registered in 35 other countries, some 70 percent could be related to Dutch criminal organizations. Of the 205 Dutch seizures, 141 involved synthetic drugs that were intended to be exported. The seizures of drugs around the world that could be related to the Netherlands involved some 24.6 million MDMA tablets and over 910 kilos of MDMA power. Of this total, the largest amount was seized in the Netherlands (6.1 million pills), Belgium (more than 5 million pills), followed by Germany (almost 3 million), the U.S. (2.5 million), France (2 million) and the UK (1.8 million). The USD reported lower amphetamine seizures in 2002 than in 2001, but the quantity of Dutch-related amphetamine seized in other countries went up. In 2002, the USD dismantled 43 production sites for synthetic drugs, of which 26 were situated in residential areas. Most production sites were MDMA laboratories. According to the USD, the production of synthetic drugs in residential areas is an alarming development. The FIOD-ECD, which is primarily responsible for intercepting chemical precursors, seized some 318 liters and 9,255 kilos of PMK and 1,228 liters of BMK in 2002.

Drug use among the general population of 12 years and older, 1997 and 2001 (life-time (ever) use and last-month use)

| |

Life-time use (%) |

Last-month use (%) |

|

1997 |

2001 |

1997 |

2001 |

| Cannabis |

15.6 |

17.0 |

2.5 |

3.0 |

| Cocaine |

2.1 |

2.9 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

| Amphetamine |

1.9 |

2.6 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

| Ecstasy |

1.9 |

2.9 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

| Hallucinogens |

1.8 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| of which LSD |

1.2 |

1.0 |

— |

— |

| Mushrooms |

1.6 |

2.6 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

| Heroin |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

Drug Seizures, source Europol

|

2001 |

2002 |

| Heroin (kilos) |

739 |

1,122 |

| Cocaine (kilos) |

8,389 |

7,968 |

| Cannabis resin (kilos) |

10,972 |

32,717 |

| Herbal cannabis (kilos) |

22,447 |

9,958 |

| Ecstasy (tablets) |

3,684,505 |

6,878,167 |

| Amphetamine (kilos) |

579 |

481 |

| LSD (doses) |

28,731 |

355 |

Cable Reference ID 04THEHAGUE4, 2004-01-02, Classification UNCLASSIFIED, Origin Embassy The Hague.

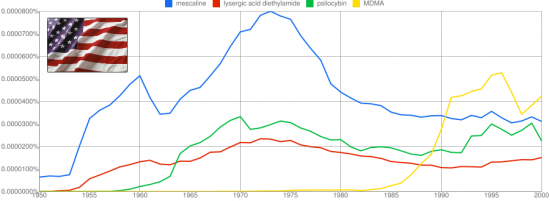

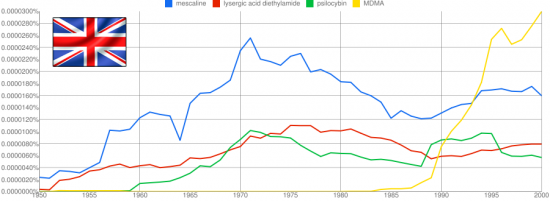

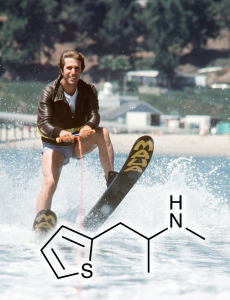

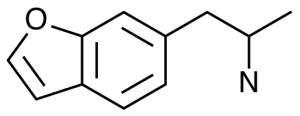

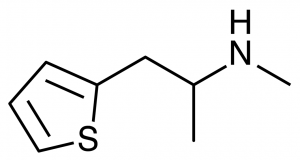

The research chemical market has exploded in recent years primarily due to the emergence of cheap euphoric stimulants produced in volume. The wide appeal and behavioral reinforcement of these compounds relative to the more niche appeal of previous psychedelic research chemicals resulted in a flood of cash from a less discerning clientele. If it made you feel good, it sold - and governments across the world quickly attempted to fill in the blanks in their legislation.

The research chemical market has exploded in recent years primarily due to the emergence of cheap euphoric stimulants produced in volume. The wide appeal and behavioral reinforcement of these compounds relative to the more niche appeal of previous psychedelic research chemicals resulted in a flood of cash from a less discerning clientele. If it made you feel good, it sold - and governments across the world quickly attempted to fill in the blanks in their legislation.