Endocannabinoids

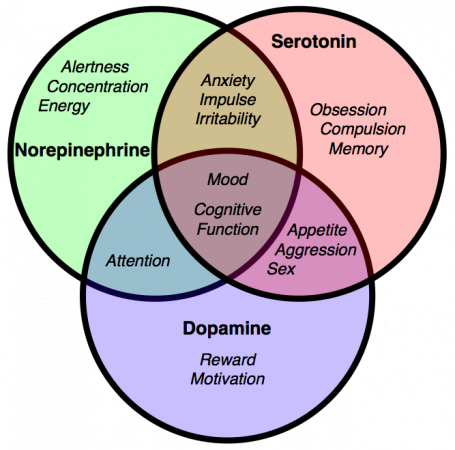

The precise mode of action of cannabis was unclear until very recently. In 1988 cannabinoid receptors were shown to exist in a rat brain, and in 1990 the locations of the cannabinoid receptor system were mapped in several mammalian species, including man. This led to the search for endogenous cannabinoids (endocannabinoids), natural compounds synthesized within the brain that would activate these same receptors. Several were discovered, with anandamide and 2-AG receiving the most attention. It was found that endocannabinoids operate via retrograde signalling, where a signal travels in reverse from a postsynaptic neuron to a presynaptic one. Unlike other neurotransmitters such as the monoamines which are stored in vesicles for eventual release after synthesis, endocannabinoids are created “on demand” by enzymes as required.

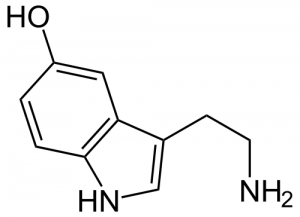

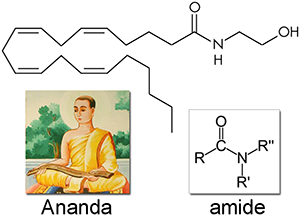

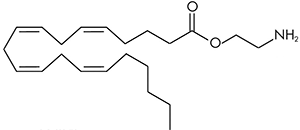

Anandamide (AEA) was first isolated in 1992 and named after ananda, the Sanskrit word for bliss, and the amide chemical backbone. Like all of the endocannabinoids, it is made from arachidonic acid in our bodies, an essential polyunsaturated omega-6 fatty acid that must be consumed as part of a complete diet. Anandamide is a full agonist at CB1 receptors with a potency comparable to THC, and a partial agonist at CB2 receptors. It is very common, found in nearly all tissues and in a wide range of animals.

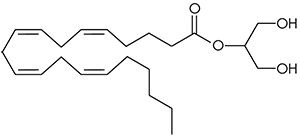

2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG). No one really wants to admit it since anandamide was discovered first and has such a great name, but 2-arachidonoyl glycerol is probably chiefly responsible for endocannabinoid signaling. A full agonist at both CB1 and CB2 receptors, it is capable of stimulating higher G-protein activation and is present at significantly higher concentrations in the brain than anandamide.

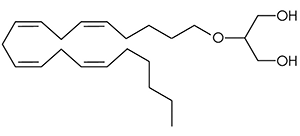

2-arachidonyl glyceryl ether (noladin ether) was first discovered in the brain tissue of a pig in 2001, and prior to this had been synthesized in a lab as a closely related analog of 2-AG. It binds primarily to the CB1 receptor with weak agonism at the CB2 receptor, and is more metabolically stable than 2-AG resulting in a longer half life.

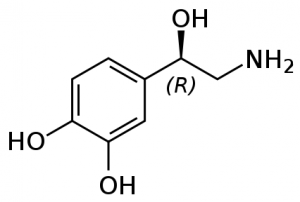

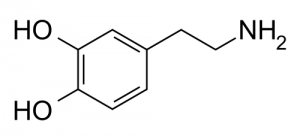

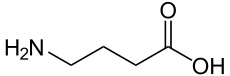

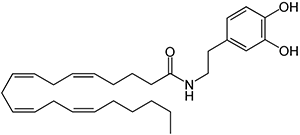

N-arachidonoyl-dopamine (NADA) Discovered in 2000 in the brain of rats, NADA preferentially binds to the CB1 receptor with no action at dopamine receptors. It the amide of the neurotransmitter dopamine and arachidonic acid, as well as a potent inhibitor of the growth of breast cancer cells.

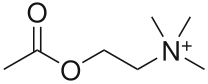

Virodhamine (OAE) can be thought of as similar in structure to anandamide where the nitrogen and oxygen atoms have switched places. The molecule was therefore named virodhamine after the Sanskrit word virodha meaning opposite. It is a partial agonist at the CB1 receptor and a full agonist at the CB2 receptor. It is present in concentrations comparable to anandamide in the hippocampus, but is present much higher concentrations in peripheral tissues with CB2 receptors.